Back to Issue

The Deluge

by Rachel Ton That

The headaches are getting worse, a dull pain behind the eyes, a pressure at the temples. I rub my fingers over them but the ache remains, and with it a faint blur of vision.

Staring at the plain oak table before me, I examine its grain, gold and brown brindled and running two ways. The wood remains singular and blessedly still until my eyes water and I look away to the whitewashed wall. To my eyes the wall appears dappled, clean white with patches of rot and ruin, and a few rare gaps where there is no wall, where it has collapsed into rubble. When I look back at the table it appears in its usual riot of growth and decay. Branches sprout buds, termites fester in blighted wood, and my head pounds.

I could lie down, take more poppy, but instead I sit in the garden and wait. Every evening my neighbor comes to call, pushing open the wicker gate between our homes. In the stillness I hear his footsteps on the grass. Far-sight, he shouts to me, his private jest. He is a wheelwright, and I, a diviner.

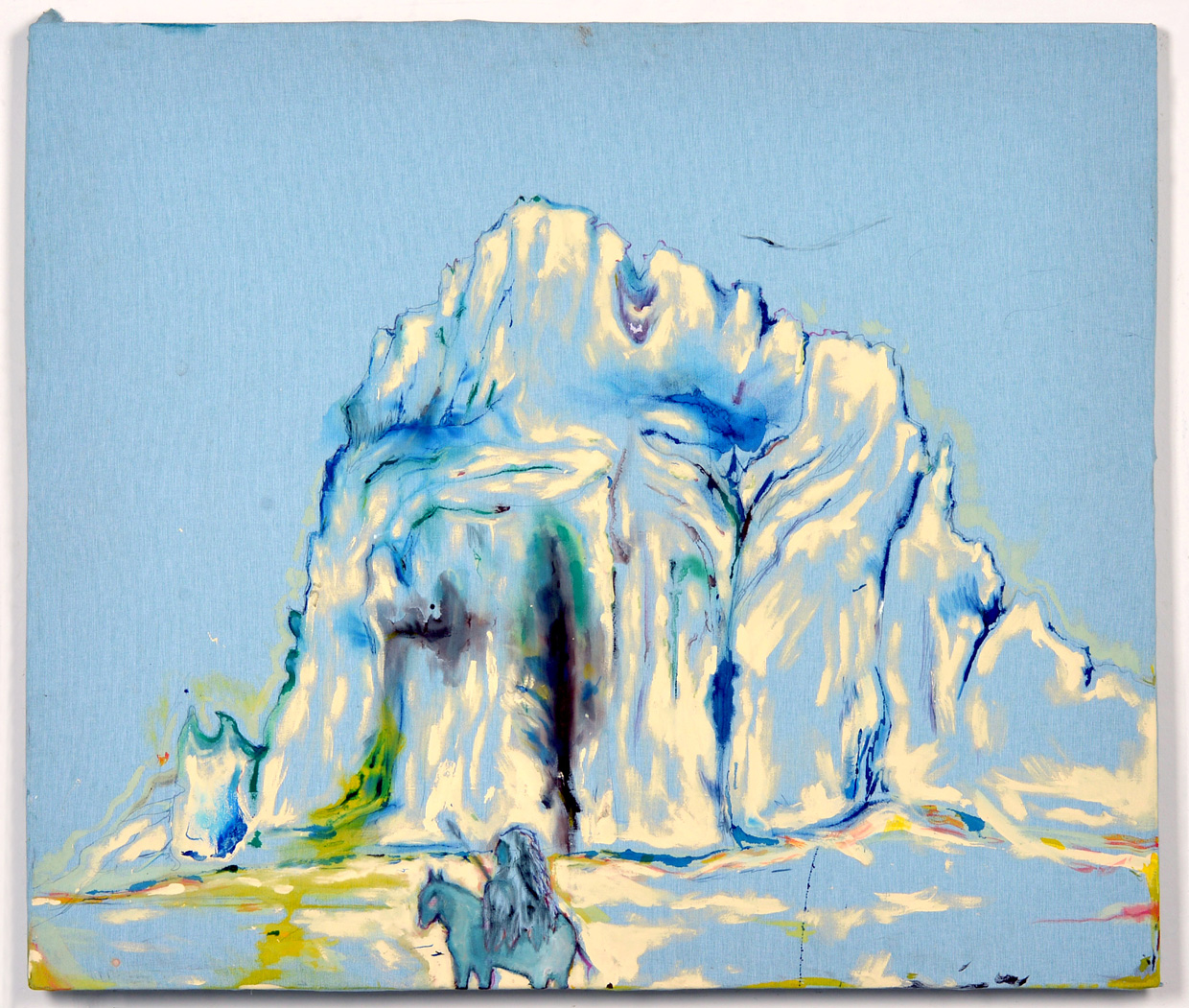

We sit and share a small flask and look out at the mountains. They rise, immense, blue-green on the horizon, surrounding the valley. Some days they are clear silhouettes, on others, shrouded by mist.

How goes the world? I ask, as always.

The world turns on the spin of a coin, he says tonight. Sometimes he says, the winds rush over the still of a cartwheel, or seas rise on the breath of the earth, and so on.

There are evenings when we talk about the valley, this year’s crops or the caravans that come through and what they might bring. But most evenings we keep silence together, side by side, looking out over the mountains. Nature’s changes are less varied than the changes of man or his inventions. The grass flickers yellow to green, the trees appear wreathed in leaves or without, the sky reveals itself to me in a thousand shades of blue and red, but in this I find peace. By the time he leaves the sun has set, but the pounding of my head persists.

The fisher-girl is a wise woman on the side. In the pungent dim of her house I stoop a little, head bowed under the low roof as she stirs her potions. A half spear of rosemary, a twist of rosehip, a star of marigold. She crushes them beneath the pestle and makes a paste to apply at the temples and throat. She gives me an infusion of valerian to drink before bed.

I take it with thanks and, as payment, I inspect her foundation, shifted in part by the heavy summer rain, and in part by the malleable clay of the soil. It will hold for another year but no longer. She says she will leave before the stones slip, and I go out into the night back home, anoint myself in her brews, and down the valerian, but in bed I toss and turn. My head feels heavy and feverish to the touch.

My only relief is flesh.

I leave my hot pallet and go out into the night, to the row of houses where a woman can be bought. There is only one door I knock on, and she opens it eagerly as if we had set a time and she has been waiting for me.

She is not the most beautiful, but her future is the brightest. When I run my hands over her skin I can feel her future happiness just beneath the surface. I bite her lips and taste the wine she will drink at her wedding. I kiss her palms and feel the flour she will knead in her kitchen. Once, resting my head on her hip, I saw her son, small at first, growing strong and beautiful before my eyes. But I do not tell her. She expects nothing from the world; her pleasure will be much greater for the surprise.

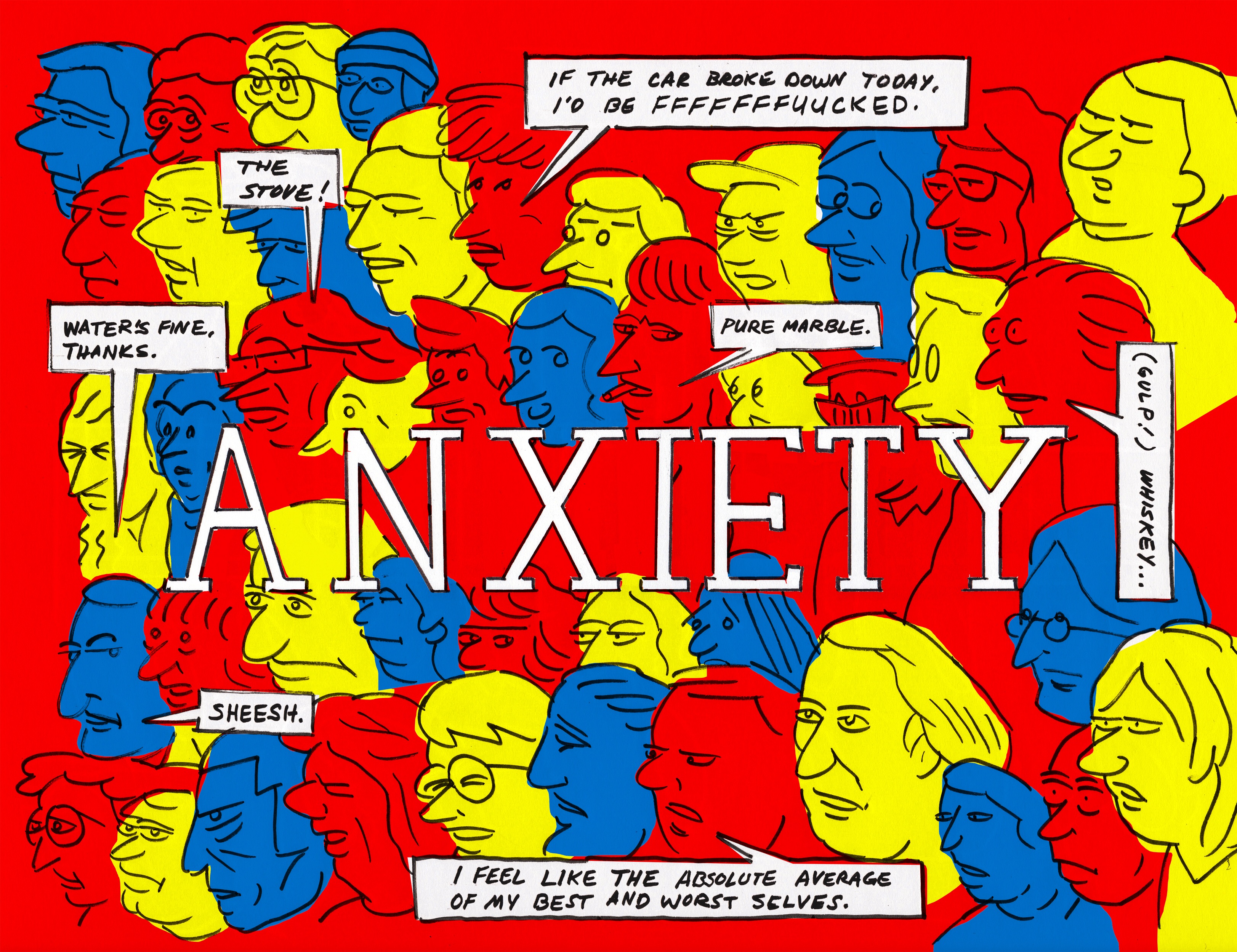

∆˘

When I was a child I thought my sight no different than others, though the world was blooming around me, ever shifting between time. I would watch days ebb, fade, and renew in a single moment; sunlight blushed rose through the window and then dimmed. Objects were created before my eyes, wore down, faded to dust. At times it felt as if I were in the center of a maelstrom, inside the eye, dazed and bewildered from the constant flood of images, scents, tastes and sensations that encompassed me. The present that I inhabited was sometimes blurred, lost in an inundation of other times.

Whenever I became overwhelmed I used to take my hands and press them together, or trace the outline of my palms, feeling my own skin beneath my fingertips. I had discovered that my physical self was my only tether, the only thing fixing me to the present. These days I clench my fists or bite the inside of my mouth, sometimes hard enough to draw blood. Pain or pleasure brings me back myself, helps ground me in the substantial, but there are nights when I wonder if one day the world around me will dissolve to chaos, if the tether will break and my mind will follow.

Diviners are not uncommon, but there are fewer now than there used to be. I have only met one other, the man who found me. Like the goatherd or the manservant, my role is a modest one. I do not create things or provide food, but tend to that which is already present, as a kind of caretaker. The world is changing and I have seen my part in it diminish. Some would rather live without my telling of past and future, would rather put their trust in that which can be measured and quantified. For now, the villagers consult me, but keep their distance.

∆˘

I have been requested in the fields this morning, so I take a round of brown bread from the cupboard and eat as I walk the long road south to the last farm, tearing it to pieces with my fingers, and scattering the crumbs in the dust for the birds. The air is clear and cool, the breeze so slight it barely ruffles the leaves. My headache is almost gone. When I reach the gate I enter it, for I know him well, and walk to his door and knock.

His wife opens the door.

Come in, she says kindly.

She takes me into the kitchen, its floor laid with new pine. I try not to look down at my feet mired in leaves, but I can feel the uneven branches bend beneath my weight. She puts a cup of hot tea in my hands before putting me on the path to the fields.

He is kneeling in the dirt, probing the roots of the wheat. When he sees me he stands and brushes the soil from his clothes; he clasps my hand with his.

It is well that you could come, he says, laughing, I need better eyes than mine.

The fields are awash with emerald, gilt, and brown, the stalks high, then shorn. I look over them, observing the crops from the last few years before selecting a single plant. The wheat is young, a slender shoot capped with the first tuft of grain. It reveals itself to me from and I focus my sight so deeply that I find myself inside it, feeling its quick green life and hunger for growth. The soil is rich and mixed with clay, the water plentiful. The seedling grows into a golden stalk, reaching for the sun. Even as dusk falls it looks to the moon, breathing in the night air. I pause at this future, savoring the cool of the evening.

Something draws near in the darkness. I cannot see it yet, but it lingers on the edge of my senses, its presence filling me with unease. As I strain my eyes through the gloomy fields, an unnatural glow appears and grows brighter. It flickers closer, bringing with it a terrible heat. Flames emerge from the undergrowth, feasting on the field. They feed their way to my stalk of wheat, licking at its leaves, and there is only pain, unbearable pain. The wheat is consumed, yet my skin burns, pain lances up my own limbs.

I start from my reverie with a cry and touch my arms, my face. My skin is red and hot, my fingers feel as if they have been seared.

What did you see? he asks, frightened. He pulls me to sit down and wets a cloth with his flask, handing me the damp rag. I press it to my face and wait until my skin has cooled.

Fire, I say. Tell the others. The fields will burn.

He questions me for some time, but I cannot tell him when, only soon. He looks at me with worry and fear, but pays me in salt before I leave.

The vision continues though I grip my hands so tightly that my nails gouge my palms. I walk back slowly through blackened fields, my feet carrying me home through a thick layer of ash. It is only after midday, but I mix poppy with honey and swallow it before taking to bed.

∆˘

I dream of fire, as I have every night since the fields. I wake up sweat-soaked, burning up. I beg more potions from the fisher-girl, but after I spend my last measure of salt on a vial of poppy, I am forced to return to town for another seeing.

I have always kept my eyes on the ground, but now I do so fervently, avoiding the fields, sweeping only cursory glances over my surroundings. As I have ever since I was young, I wish to come and go with my eyes closed. Even if I cannot shut out the scent and feel of other times, at least the multiplicity of images would still.

Today I search the flocks for disease. The tradesmen and shepherds let their sheep mingle while I walk through, searching for impending maladies. I have watched the flocks shrink in winter and swell in spring. The flock is docile today, grazing calmly on the tender wildflowers. Errant lambs wander in ever widening circles from their mothers.

Among the scents of meadow grass and sorrel comes more acrid smell. Too late do I sense the vision coming over me, and in an instant the world around me turns dark, day to night, grass to flames. The air fills with smoke. The flock is mad with panic, they cry out in hoarse ovine voices as the fire encircles them, their screams echo in my ears. The young succumb first. Fire crawls up their limbs, alighting on their woolen coats, burning voraciously through muscle and sinew, down to the bone. The others soon succumb, some running madly through the blazing fields, their bodies half eaten by fire, their skeletons exposed and spectral. The smell of burning flesh fills the night.

I wrench myself from this nightmare, beating my own clothes to put out the flames, though there are none, cradling my blistered hands. The other men around only look at me in askance, exchanging glances.

Fire, I shout, A great fire is coming.

I hold up my hands as proof.

There is a silence, deafening, and then a murmur of laughter.

What fire is this, diviner? Asks one of the shepherds. When shall it come, and from where?

I do not know, I say. The bones of my hands throb. I have seen it before, three days past, in the fields and every night since. Your crops will be blackened by fire and grayed by ash. Your sheep will be consumed. I have not seen our fates yet, but I fear to.

There is a whisper of voices, a rush of fear, but a younger man steps forward, the son of a tradesman.

Why should we believe him? What signs of fire have come from the mountains? And what fire could be great enough to devour us all?

There is a pause, the people whisper together, looking at me from the corners of their eyes.

The speaker of the market steps forward.

“Diviner, we take your council, but we will wait on it. Let scouts check the brush on the mountains. Until then we will remain calm.”

Slowly the men pay me what they owe, some grudgingly. I cannot conceal the trembling of my hands, but I take the salt and food and put it into my pack. I walk home, an older man.

Potions offer no relief, but I put a balm on my hands. After dark I walk, head bowed, to her house.

Inside, I pull her dress until it falls from one shoulder, and then the other. Hungrily, I reach for her, for the flesh that gives under the touch of my hand, the skin that melts under my tongue. She wraps her arms around me and I bury myself in her skin.

∆˘

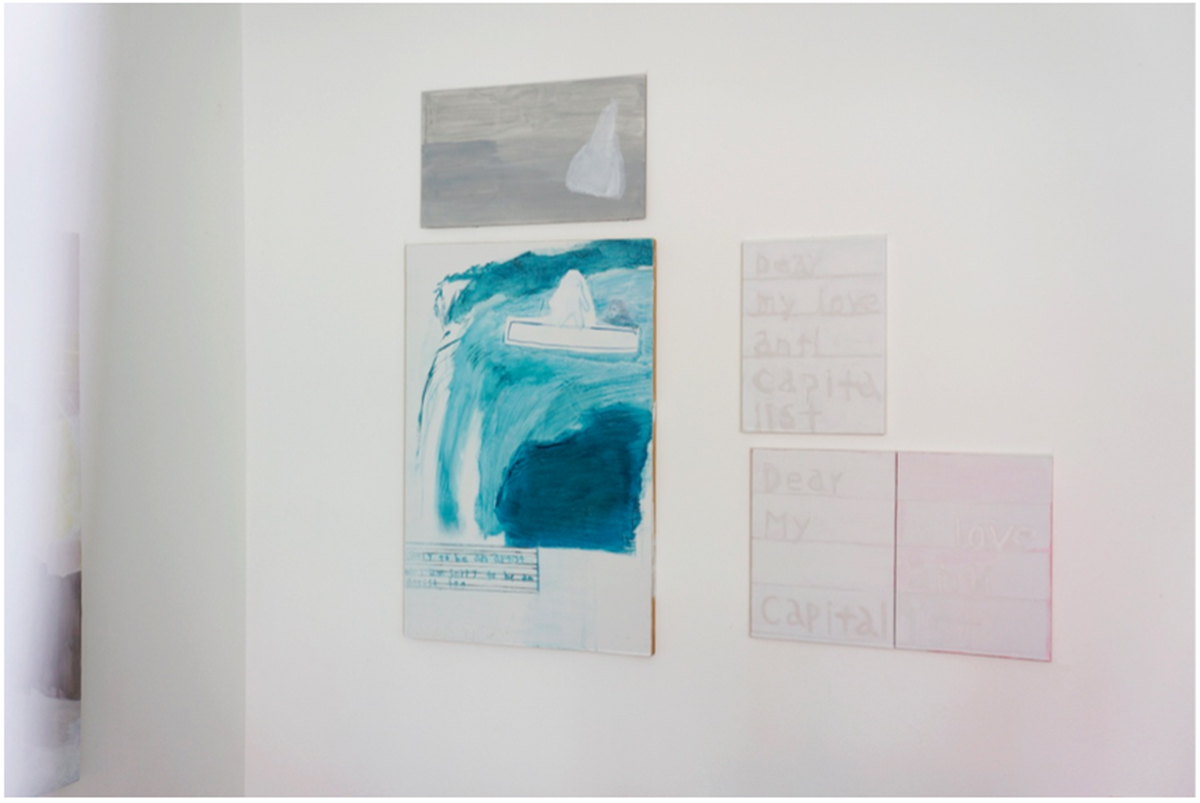

For the last three days I have pleaded sick, and the town goes on without me, no firebreaks have been dug, no scouts have been sent. I lie in bed, staring at the flat, whitewashed surface of the wall. It is charred and black. Visions of fire consume me: flames sear the walls, rubble is reduced to embers.

The face in the mirror is sick and gaunt. My cheeks burn with fever, my eyes are glassy. I have no more poppy or potions, so I pull on a faded shirt and make my way to town.

She opens the door as always, but her eyes are worried. I take her in my arms and kiss her as though it is our last kiss, as if this is the last night. She presses herself to me, the softness of her giving against me. I try to lose myself in her skin, but all I can smell is fire, the smoke burning through my nostrils, leaving the scent of charred flesh and singed hair. I touch her skin but black flakes cling to my hands, her hair crumbles to ash. I hold onto her face like a drowning man, forcing my eyes to see her—eyes closed, lips parted, drawing in quick, shallow breaths. I rest my forehead against her cheek, put my lips to her brow, but her bones rise up against the skin and her skull is in my hands, black against the night.

I tear myself away from her corpse and run out into the darkness, the smell of ash and death clinging to me. At home I sit at the table, head in hands, until at last I drift off to sleep, my cheek against the wood.

I wake in late afternoon. The headache has faded, my skin is cool. I drink some water and go out into the garden.

It is early yet, he has not come, but I sit outside and let the waning sun sear my skin. The air is warm, and the breeze is scented with green and gold. The valley is still. Even the soughing of the wind is subdued. Above the mountains, the sky is clear and still bright, shifting to a deeper azure as the sun begins its descent. The horizon is a smooth, unbroken line.

Near the edge of the mountains a dark cloud gathers, duskier than a storm. It grows and stretches over the edge of the mountain until it thickens into smoke, and bright glints can be seen lighting the trees. The smoke rolls down, roiling and billowing. The trees catch fire, one by one, their trunks burning down to charcoal. The fire advances, eager and ravenous and backed by the wind, until the mountains themselves are ablaze with crimson and ochre. The world is in flames.

Rachel TonThat is a film photographer, multimedia artist, and fiction writer living in Taipei, Taiwan. Her stories draw from folk tales, myth, and oral storytelling. Rachel is the co-author and co-creator of the the artist book, Lost Cities. She is a graduate of Eugene Lang College and Parsons School of Design in New York.