Back to Issue

Imagination and Blind Perception

by Sam Swasey

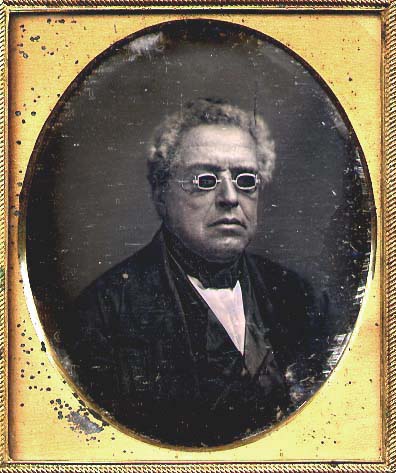

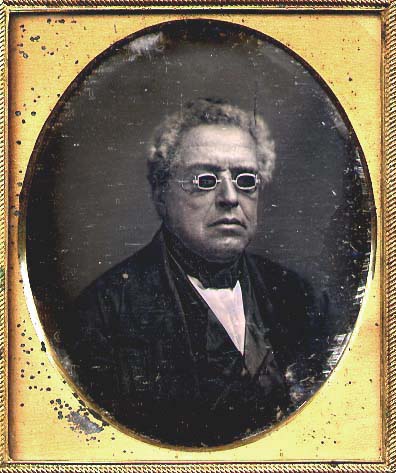

Artist unknown, Untitled, 1850s, U.S.A, Courtesy of Vintage Works, Ltd and I Photo Central, LLC www.iphoto.com

Photography literally means “drawing with light.” Named this way in the early part of the 19th century when the technology was invented, the camera, it seems, was once perceived to have a different connection with what was located in the viewfinder. Nothing was “captured” or “taken” like some sort of fractional piece of reality held hostage inside itself. Rather, the photograph, as with its predecessors of documentation, was simply sketched, drafted, or drawn. Yet unlike the drawings of previous centuries, the image was not brought into being by the hand of an artist. It was as if light itself traced the lines and contours of the scene and recalled, like a vivid memory, a reflection of the past and seemingly the reality of what was.

Compelled by a desire to verify their own existence, or, at the very least to leave something of themselves behind for future generations, Europeans and Americans flocked to Daguerreotype photography studios during the latter part of the 19th Century.

The blind went too. Perhaps they wished to leave behind an artifact containing their visual appearance, a testament to a reality that they could not perceive. Or maybe it was their desire to hold the photographic reproduction, to grasp with their hands that which they could not see with their eyes. Or perhaps it was by way of their image contained within the photographic frame that they, though unable to experience it, could participate in a reality that was no longer, if ever, their own.

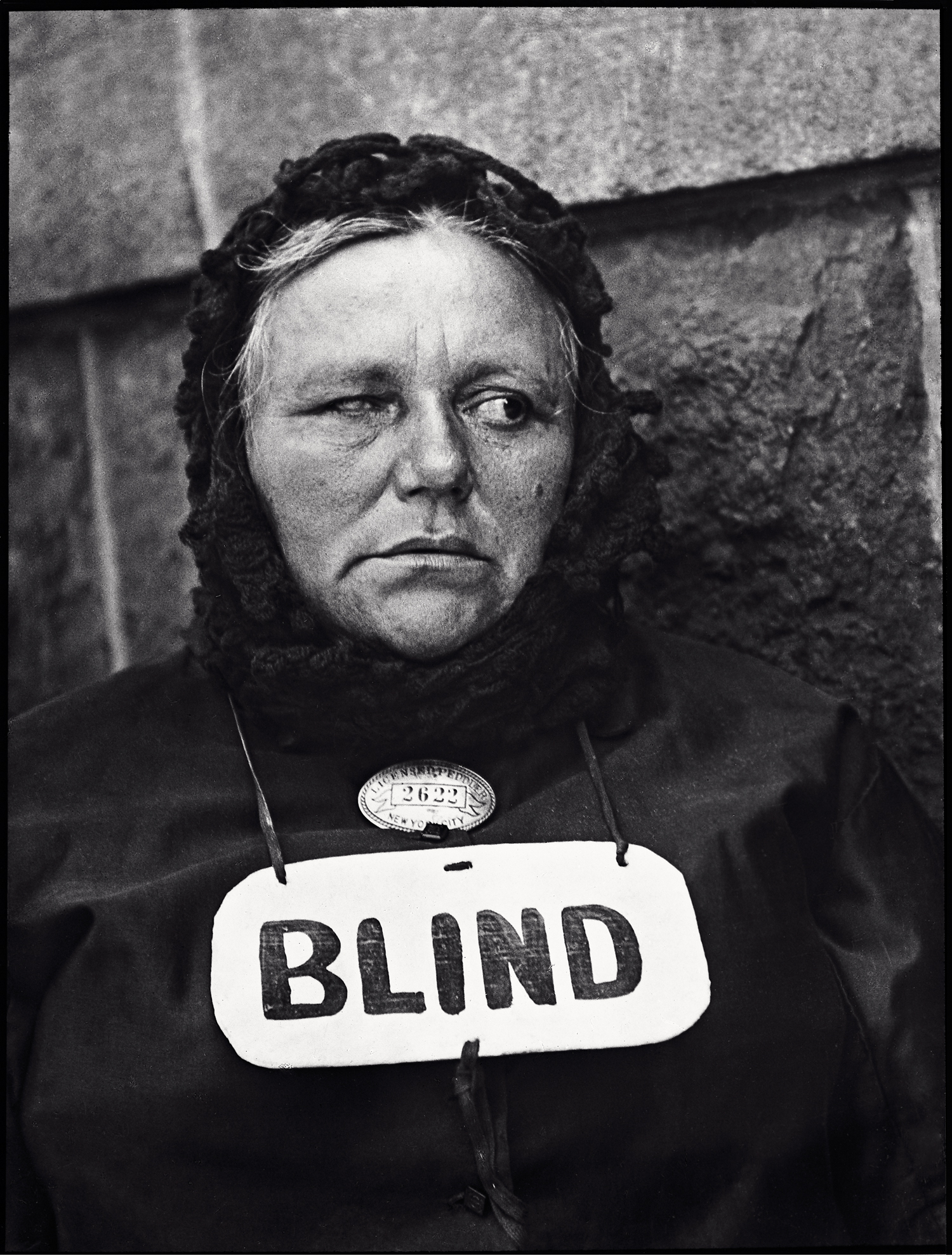

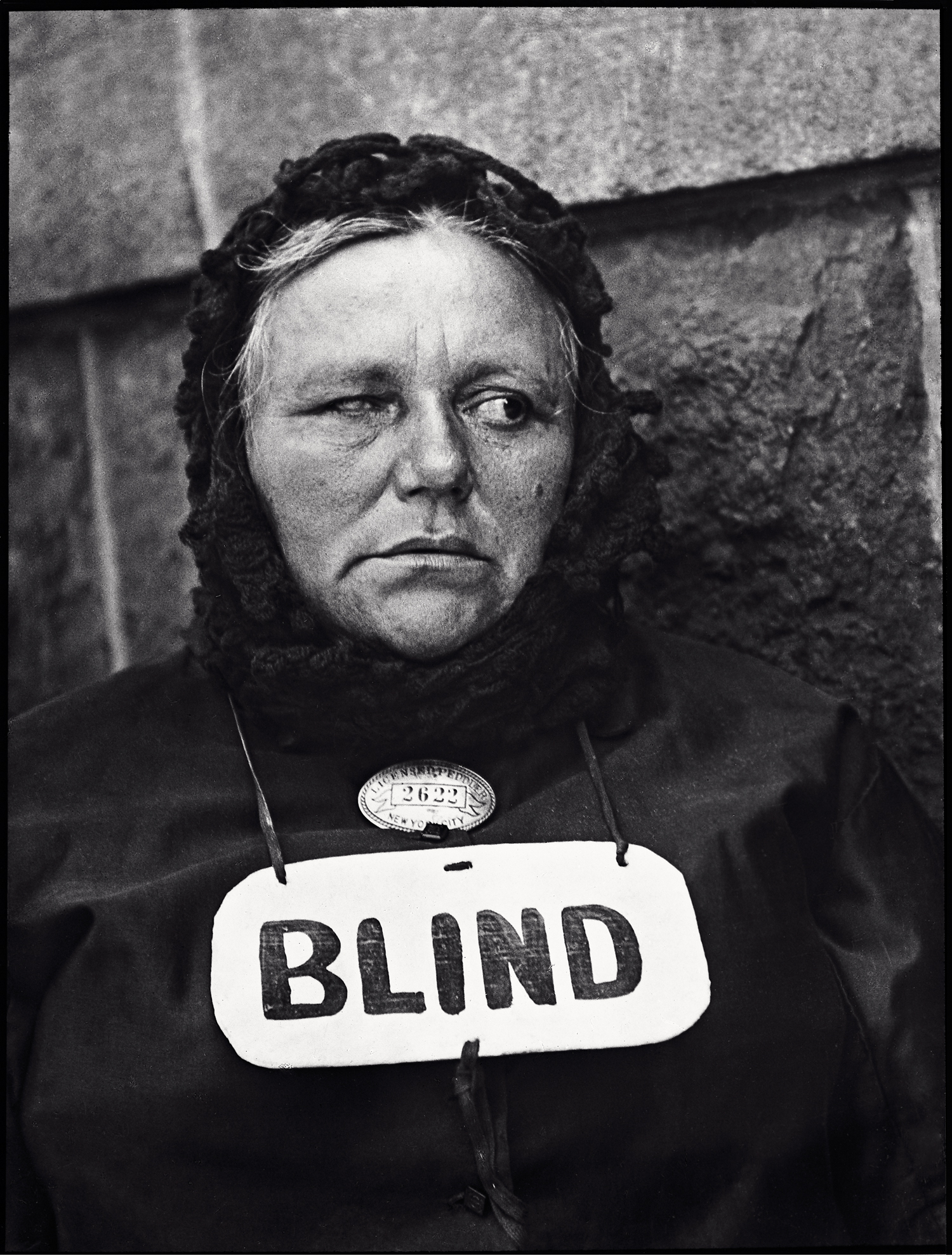

Conversely, it might be this paradoxical desire that has compelled photographers throughout the centuries to attempt to make visible the invisible, to capture the un-seeable secrets in the faces of the blind. In Paul Strand’s photograph from 1916, Blind Woman, New York, an aged woman stands against a stone wall. We are certain of her bodily deficiency for around her neck she wears a sign that reads “BLIND.”

Paul Strand, Blind Woman, New York, 1916. Copyright © Aperture Foundation, Inc., Paul Strand Archive.

Though she cannot see this sign that is indicative of her bodily impairment, she feels its significance as a gentle weight around her neck. It rests on her chest attached to strings in a way that glasses might for someone with functioning eyes. Closer to her throat and composed of a soft glow reminiscent of the twinkle in her sideways eye is a badge that reads “Licensed Peddler 2622.” In the years after the Civil War, when amputees and the war-torn insane returned to their city, New York had established the right for the physically and mentally afflicted to sleep at night in certain public parks, giving them various jobs as street vendors as well. What her job was we cannot know, and just as she could not see the world around her, we cannot hear the sounds she heard.

Perhaps she stands down on or around The Bowery—a location Strand photographed often—where recent immigrants, drunks, and drifters often congregated and lived, drawn in by vice and poverty. In this case, she might have heard belching men cat-calling prostitutes, the hum up above of conversing people squeezed into all-too crowded tenements, flies that buzzed and lingered around puddles that formed in the streets, or the snore of a sleeping man curled up in a darkened hollow like some forgotten pup. Had we been there when the photograph was taken we might have heard far different things, busy with our eyes and all that was there to be witnessed.

We see her as she has never seen herself, while she perceives the world as we never have. “It was only by deceiving his subjects,” wrote Geoff Dyer in his book, The Ongoing Moment, “that [Strand] could be faithful to them.” Though in the case of the blind woman, her sense of self is anything but an appearance attained through ocular perception, whether that be the eyes or lens. It is not she, but the viewer who is deceived. This image does not move us for what it contains, it moves us for what it does not contain, that which we cannot see or grasp—the absence of vision. She perceives what we cannot—the subject of the image: blindness. Whereas we see what she cannot perceive—the visual form, her appearance, which is suggestive of the subject. It is an image which is nearly negated by absence, but which is effective precisely because of this negation.

In Strand’s photograph we find both hardship and poverty but also something beyond us, something ungraspable. It compels us to question the significance of another’s gaze. There are the dreamer’s eyes that are at times far off and vacant and at other times concrete and penetrating, the “pale blue eyes” so often spoken of in song, red eyes aflame in life’s struggle and blind eyes that forbid us entrance—instead our gaze spreads like wax over their empty hemispheres. For centuries the blind, not unlike artists, have been thought of and discussed on two divergent levels: on one they are pitied as melancholic outcasts somewhere between bohemian and beggar and on the other they are glorified as visionaries somewhere between human and god.

Imagination is inextricably connected to the image (imago) and therefore to vision, thus blind eyes defy us, for what is absent cannot be imagined. Conversely when vision goes missing from those afflicted with blindness, they are at times throughout history described not as losing, but in fact gaining something. In the Matrix Trilogy, for instance, Neo faces the recurring conundrum that what he, and likewise, what we are seeing is not actually what is. In the final fight of the third film he is blinded. Before winning the fight with the swing of a blunt metal object he states, as if astonished, “I can see you.” Though visually blind he can, in a sense, see beyond the virtual sleights, or rather, because he cannot see, he is unaffected by them and therefore perceives the world as it really is. Phenomenologist, Maurice Merleau-Ponty wrote that,

More directly than any other dimensions of space depth forces us to reject the preconceived notion of the world and rediscover the primordial experience from which it springs: it is, so to speak, the most ‘existential’ of all dimensions, because… it is not impressed upon the object itself, it quite clearly belongs to the perspective and not to things.

Our conception of depth is “primordial” and not directly related to sight. If we were blind suggested Merleau-Ponty, a walking stick would be used to “mark, in our vicinity, the varying range of our aims and gestures…to incorporate them into the bulk of our own body.” Though in the case of the Greek prophet Tiresias, his useless eyes, which prevent him from fragmenting the world into objects and visual planes of depth, allow him to perceive eternity in a single instant. Subsequently he dismantles his findings and composes them in the fragmentary language of his listeners. It is as if he can momentarily vanquish any conception of space or depth from his being to perceive the pure duration of existence—to separate space from time.

Neo and Tiresias fascinate us not because they, as the story often goes, overcome their bodily afflictions, but because they perceive the world differently. Their perception of the world is potentially more acute, their imagination more powerful and their conception of an objective reality more complete.

During the Middle Ages it was believed that something called the pneuma played a vital role in perception and more specifically vision. The pneuma, according to William of St. Thierry, acted as an “intermediary between the spirit [or the breath of God] and the body.” When viewing a painting, the pneuma exited the pupil of the spectator, made contact with the color and form of the art object and returned to the eye to activate the imagination. Like the observed similarities found in contemporary science between the orbiting of electrons around the nucleus and the planets around the sun, the microcosmic systems of perception during the Middle Ages—namely vision—mirrored the macrocosmic system connecting the Medieval God to all beings on Earth. Accordingly, when a child was born the pneuma left the body and travelled upwards to the heavens to collect the spirit of God. After returning to earth and entering the child, the soul was “originated” or activated, much like the imagination of the spectator who ponders a painting on a wall.

The idea of an outside element or a spirit that stimulates artistic innovation is ever-present. From the inspiration Woody Allen has claimed to have derived from his relationship with Diane Keaton, Mariel Hemingway, Scarlett Johansson etc.; to the over-powering, nauseating, and erotic inspirational effect the young Polish boy, Tadzio, has on the protagonist, Gustav von Aschenbach, of Thomas Mann’s Novella “Death In Venice”; to Beatrice, the both Godly and (arguably) erotic source of inspiration for the Pilgrim in Dante’s Divine Comedy. The muse, though forever changing in formal appearance, has occupied a permanent and, for the most part, uncontested aspect of artistic production for centuries.

In the Divine Comedy, the Pilgrim enamored with the appearance of Beatrice, often, though ineffectually, attempts to put her beauty to words. In Canto XXXI of Purgatorio he exclaims:

o splendour of eternal light,

who’s ever grown so pale beneath Parnassus’

shade or has drunk so deeply from its fountain,

that he’d not seem to have his mind confounded.

Later, while in Paradise, the Pilgrim states “now I must desist from this pursuit in verses, of her loveliness, just as/ each artist who has reached his limit must.” The Pilgrim is “cofounded” in both instances, unable to put to words the beauty that stands in front of him. However, it is not the beautiful essence of Beatrice or a profundity attributable to an aesthetics of the body that confounds.It is the light of God—“the breath that animates [everything]” and “the love that moves the sun and the other stars”—that leaves the Pilgrim speechless. Beatrice, while in Purgatory is geographically distant from the heavenly realm of God—the realm of unbounded love. The beauty that emanates from her is not simply a reflection of nearby Godly rays of light, but rather an internal combustion of sorts, because she is always spiritually close to God and permanently aglow with his love. This concept, if related to the work of art, implies that the closer the work is to God spiritually the more love it radiates and the more breathtaking it is. When the visual pneuma receives the essence of God reflected from a profound work of art, the more Godly the viewer becomes for the moment he has the image in his gaze, the more love he is filled with and the more powerful the workings of his imagination grow.

This phenomenon likewise occurs when an artist experiences moments of epiphany. When all disjointed aspects of the universe and human consciousness seem briefly to align, he too might be described as momentarily making contact with God—his mind clarified and moved by unbounded love. Though the source location is reversed from heaven to hell, this is perhaps the root from which the belief came that the violinist Nicolò Paganini and guitarist Robert Johnson sold their souls to the devil in order to achieve musical virtuosity. The former God-related belief certainly has close ties to the concept that those with the greatest imagination, and for our purposes artists, are perpetually plagued by depression. The untimely deaths of artists by way of alcohol, drugs, and suicide, from Van Gogh to Kurt Cobain, Mark Rothko to Amy Winehouse (etc.) corresponds with this early medieval logic. This is not to say that all artists are depressed, or that each death by suicide or misadventure derives from identical sources. But according to the logic of Medieval hermeticism, the more profound the artist’s idea or work of art is, the more Godly they momentarily become and the more they are filled with love. But also, as the epiphanic opening is sealed over once more, the further they fall from grace and the more deprived, depressed, and even wretched they might become.

Artists, like the blind, have historically been deified because their vision of the world is thought to surpass our own; it is otherworldly, supernatural. Conversely they are pitied because if this vision is to be contemplated by us, it must be dissected and understood, fall and fragment—like the artist’s thought and wellbeing—to a place of simplified human cognition. Pablo Picasso once said that “they should put out the eyes of painters, as they do with goldfinches to make them sing better.” It might be that a perception of the world unobstructed visually by concrete objects creates an imagination that is more powerful, closer to God, and composed of greater love. In the case of Neo or Tiresias, this perception allows them to see the world as it actually is.

Between 1980 and 1981 Bruce Davidson photographed a different blind woman. She, like the subject of Walker Evans’s photograph, New York (25 February 1938), plays an accordion in an aisle of a subway car. In this photographic space where time does not pass through, but around, her being and the music she played have no medium on which to be carried; they are objectified and silenced. She will hold this inaudible note forever, her vision of the world hidden like secrets between her fingertips and the keys. In his famous poem “Ode On A Grecian Urn” John Keats wrote “heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter.”

It is a line that is suggestive of the conceptual underpinnings of the Romantic school of thought and their belief that it was the creative spirit of the artistic genius and not the created byproducts of that spirit (their photographs, paintings etc.) that was the true art to be contemplated and celebrated. When we view these photographs—both Strand’s and Davidson’s—we can imagine what the women’s shawls might feel like if they instead hugged our heads tightly. We can almost feel the texture of the stone wall beneath our fingertips and imagine the whine of the accordion gasping. But what confronts us most directly in these images we are unable to perceive. The subject of these photographs—blindness—like Keats’s sweet melody goes unheard, unseen. Photographs of the blind evade us like a mystery and astonish because what they contain is potentially greater than us. In a sense, they expose us to our own inability to see.