Back to Issue

Ritual Image

by Robyn Barrow

An illuminated woman scurries through Stowe MS 17, a small, 14th century Book of Hours now housed in the British Library♦. The codex is a richly decorated mélange of the sacred and the profane, with costumed baboons and hybrid monsters dancing in the margins of earnest prayers to the Virgin♦. Constant like this clash of comic beasts and devout worship is the lady, ambling through the pages like they were rooms in her home. Seated in tiny architectural frames or kneeling in brightly painted clothes beside the full-page miniatures that begin the prayers—which are divided into hours of the day—the noblewoman is pictured ten times. She shares space with the Virgin and is witness to the Passion Cycle, a series of images depicting the Crucifixion of Christ♦. Though not a portrait, this figure was a visual signifier of the original owner of the manuscript and possessed a kind of totemic resonance. The owner’s painted counterpart conveyed her daily♦ devotion to the texts in her book.

The Book of Hours was an incredibly successful genre in the 14th and 15th centuries across Western Europe, but particularly in the early years of their popularity, the books were unique, and the text and images were selected for a particular person or community’s use♦. The books represent a commercial and religious conversation between patron, artist, and clergy. Stowe MS 17, then, is intrinsically tied to the woman for whom it was made, to the context of her life, and to the daily ritual of her worship. Like a flower pressed between pages, the original owner of the manuscript survives in relic form, with traces of both her cultural and personal memory preserved. Stowe MS 17 remains as an artifact to a repetitive framework of piety; this text was designed to be absorbed, rehashed, and considered through daily observance.

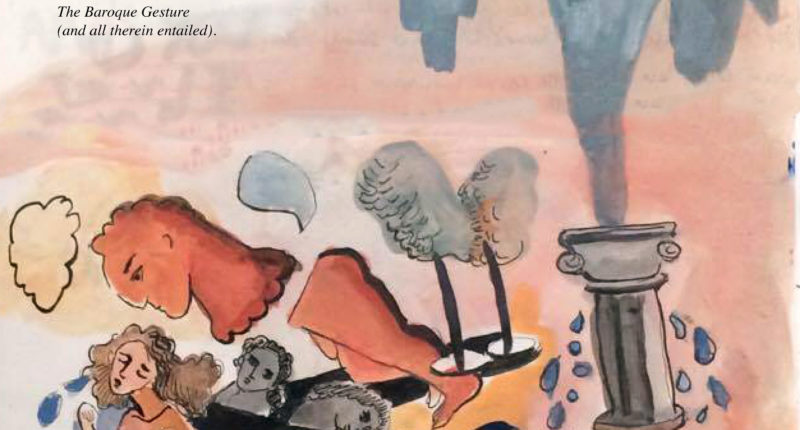

This repetition of prayer might have created for a 14th century woman a space of self-actualization that was otherwise unavailable to her. Consider the full-page miniature on the verso of folio 157, which precedes the Gradual Psalms♦. Of the twelve images in the book’s cycle of full-page miniatures, this one alone does not feature a biblical or apocryphal scene. Folio 157 visualizes the owner of the manuscript in her rich, fur-lined cloak set against a bold blue background. The space is held up by delicate golden colonettes, the field energized by the contrast of geometric reds and blues. The owner kneels at her prie-dieu, a table covered with embroidered altarcloth that falls naturalistically, undulating as if in a light breeze. Eyes raised and hands clapsed, she prays to an icon of the crucified Christ, who seems to return her gaze.

It is an image designed to be seen up-close, held in the hands and perused for a long time, many times over. Like all the Stowe MS 17 images, it was incredibly costly to make. The parchment is very fine, and adorned with significant passages of gold leaf. A multitude of pigments were used, including two shades of precious blue, both made from lapis lazuli imported from the Middle East. These materials were chosen to capture and hold the eye through repeated viewings. Beyond the supply cost, the time taken on this image would have been significant. Working on a miniscule scale, the artist demonstrates tremendous precision. Time was taken in rendering the vair-lining of the woman’s cloak, as well as its delicate folds as it puddles on the floor around her. The altar cloth is also a careful study in the way fabric moves. Finely-tuned geometric patterning in the columns, architectural framing, and backgrounds lead the eye on journeys through exquisite lines and colors. The angels in the roundels each carry a specific musical instrument, calling out to the eye and the ear. It is a work of art designed to captivate and inspire daily, to uplift the mind through repeated viewings.

What would viewing such an image many times do for the owner of the manuscript? This picture is unique in the book, significant in that it alone shows the woman in a solitary act of devotion. She is the focal point, and the subject of the image is her own ritual worship. She prays not to Christ himself, as in other images in Stowe MS 17, but to an icon, demonstrating faith without seeing. It is a portrait of her own individual, unsupervised piety. Beyond this, through its size and placement, it elevates her praying act, giving it equal significance to the biblical scenes portrayed in the other miniatures. The owner kneeling at her prie-dieu is just as large, just as colorful and detailed as the image of the Crucifixion itself a few pages before. In this way, her own action of devotion is attributed the importance of biblical revelation. Her personal faith is visualized as a miracle.

To the modern mind, ideas of rote memorization or ritual repetition carry connotations of the automated and thoughtless. For the owner of a Book of Hours, many of the prayers were likely recited from memory, the images providing invigoration during a daily routine. However, medieval concepts of memory were different, with memory as an essential part of intellect and the critical step in the acquisition of knowledge. To memorize was to know, to mull over, to understand♦. To someone living in the middle ages, there would have been nothing mindless about a daily repetition of memorized prayer. Books of Hours used images combined with known texts to challenge a devotee to higher understanding and sanctity.

Though the words she recited were chosen by someone else, and were not written in her native tongue♦, the ritual of their recitation could potentially provide the owner of Stowe MS 17 with a temporal and visual space occupied exclusively by her. Contemplation of her faith and her proximity to the Almighty insisted upon some consideration of herself and her place within a universal scheme. Looking back, we can now find only traces of this woman, only guess at what her daily life might have been. But if, as a 14th century woman, her experience revolved largely around husband and household, children and social circle, the self presented by her Book of Hours might have provided a reprieve, an independence, and an opportunity for reconsideration. Already rendered subversive by the often-bawdy marginalia, Stowe MS 17 then also had the potential to inspire independent reflection, unsupervised by Church or husband, propelled by image; it could be a woman’s world.

Folio 157r, Stowe MS 17 (“The Maastricht Hours”), First quarter of the fourteenth century, Parchment, 95 x 70 mm, British Library. © The British Library Board.

- Research for this article and information provided in the footnotes are derived from my Master’s thesis “Stowe MS 17: Text, Image and the Ramifications of Female Viewership” (2016) completed at the Courtauld Institute of Art. An article version of this thesis appeared in the 2017 edition of Immediations, the Courtauld postgraduate journal.

- “Stowe MS 17,” British Library Digitised Manuscripts, http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Stowe_MS_17; Stowe 17 has often been referenced in general studies of Gothic illumination. Studied particularly for its rich variety of marginal imagery, the manuscript has appeared in a number of published works on various Gothic themes and decoration from the early 1950s to the present. Stowe 17 was most referenced by Lillian Randall in her indispensible book, Images in the Margins of Gothic Manuscripts as well as by Horst Woldemar Janson, who cited the manuscript thirteen times in his chapter on Gothic manuscripts in Ape and Ape Lore in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Most importantly for this study, Judith Oliver’s analysis of the Mosan Gothic manuscripts, Gothic Manuscript Illumination in the Diocese of Liège (c. 1250-c. 1330), provides a thorough exploration of Stowe 17 as it relates to other books of the region.

- The eleven owner portraits are located on folios 18r, 72r, 99r, 108r, 130v, 140r, 147r, 157r, 168v, 256r, 271r.

- Alexa Sand writes extensively on these ‘pre-modern’ portraits in her book Vision, Devotion and Self-Representation in Late Medieval Art, arguing that these owner portraits were part of an inward gaze, the physical eyes seeing the spiritual self (Sand 166). See also Stephen Perkinson, The Likeness of a King: A Prehistory of Portraiture in Late Medieval France (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 2009.

- Examining a Book of Hours’ liturgical ‘Use’, or the textual content of the manuscript as compared to others by region, is often an important means of analyzing where it was meant to be used. Stowe 17 is sometimes called the ‘Maastricht Hours’ due to supposed textual links to a town in the region, though there is little concrete evidence for this conventional attribution. ’Since no other ‘Use of Maastricht’ Hours survive for comparison, the attribution is not a useful label when trying to understand the texts of Stowe 17. When compared to the seventy-five documented uses on the CHD Institute for the Study of Illuminated Manuscripts in Denmark, it is most textually similar to the Use of the Carthusian Order.

- In Stowe MS 17, the Gradual Psalms are located towards the end of the Book of Hours, following the Office of the Virgin and the Penitential Psalms. The Gradual Psalms include Psalms 119-133 and begin on 158r “Canticum graduum. Ad Dominum cum tribularer clamavi …”

- For more on medieval concepts of memory, see Mary Carruthers, The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press); 2 edition. June 2, 2008.

- The contents of Books of Hours were largely derived from the psalms and written in Latin as opposed to the owner’s vernacular French, though are are two French poems at the end of Stowe MS 17. It is likely that the owner had at least some basic Latin literacy, though it is difficult now to assess how much.

Robyn Barrow received her MA in Medieval Art from the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. She is currently engaged in doctoral work at the University of Pennsylvania.